What is a trade deficit?

You buy a Turkish-made Vestel dishwasher. In the 1980s, my stepfather’s landlord replaced all the appliances with Turkish-made ones. This surprised both me and my stepfather, but they worked quite well.

You debit your bank account by $600 and you credit Vestel’s American bank account by $600. The $600 debit shows up in the balance-of-payments in the current account under “imports.” The $600 credit shows up in the financial account under “other investments.”

What happened? Well, Vestel sold you a dishwasher for $600. From your point of view, you paid for it with your cold hard cash. From Vestel’s point of view, they got cold hard cash deposited into their American bank account. But from America’s point of view, an American imported a Turkish dishwasher and financed that by having a Turkish entity lend $600 to the United States.

“Huh?” you say?

Consider what a bank account really is. When you deposit money into a bank, you’re lending that cash to the bank. It’s still your money, you’re just letting the bank use it. So when Vestel receives a $600 deposit account in exchange for that dishwasher, it’s loaning that $600 to an American bank.

When put this way, it looks pretty innocuous. But it’s still a trade deficit.

OK, what happens when Vestel takes that money back to Turkey?

Nothing. Their bank account in the United States is debited. That’s a $600 debit in the financial account. But they now have $600 in cold hard American cash. From the point of view of a Turkish entity, both the bank deposit and the cash are American assets. So when Vestel took ownership of that $600 in cash, it didn’t increase its overall claim on the United States — from its point of view the company just swapped one American asset (a bank deposit) for another (currency). From the American point of view, Vestel swapped one foreign-held liability (a deposit held at an American bank) to another foreign-held liability (Federal Reserve-issued currency).

Again, so far, so boring. But let’s keep following the money. Now let’s have Vestel deposit that $600 in a Turkish bank. Again, nothing will change from the U.S. point of view. All that happened was that the possession of the dollars switched from Vestel to the Turkish bank.

In real life, however, we know that Vestel didn’t really take six Ben Franklins and transport them across the Atlantic. So what happened in real life?

In real life, Vestel debited an American bank account and credited a Turkish one. The Turkish bank now has a $600 asset matched by a $600 deposit owed to Vestel. But what is the nature of that asset?

It’s a deposit at an American bank. Vestel didn’t withdraw cash from its U.S. bank and transfer it to a Turkish one. Rather, it transferred ownership of its American bank account to a Turkish bank for whatever reason. (Probably because it wanted lira to pay expenses and dividends back home, but we can leave that here.)

And at this point we could, if we wanted to, stop. Why? At this point a few things could happen. The company could hold the American liability indefinitely, transfer it to another foreign entity, or swap it for Turkish lira from yet another foreign party. None of these will affect the U.S. balance of payments. On the margin the latter transaction might decrease the value of the U.S. dollar a tiny bit, but the direct effect on the balance-of-payments is nil.

Speaking generally, one of two other things could happen. One is that the Turkish bank could use its U.S. bank account to buy $600 in shares, or government bonds, or some other American financial asset. All that does is change the nature of the foreign liability. The second is that the Turkish bank could use that $600 to pay the electricity bill for its New York office, or buy a nice American-made suit from Tom James. In that case, you would have a $600 export credited to America’s current account, matched by a debit showing the liquidation of the foreign liability.

Neither of those is particularly bad. So has our small micro example proved that large and persistent trade deficits aren’t a problem? Can we rest easy knowing that there is no way that the trade deficits—and the corresponding build-up of foreign-owned assets or debts owed to foreigners — could bite the country on the ass?

No.

Every micro transaction in our example makes sense and looks harmless. The balance of payments balances, the financial flows are accounted for, and no alarm bells ring. But when those transactions repeat year after year, decade after decade, they accumulate — not just on spreadsheets, but in the real economy. The United States ends up owing more to the rest of the world, and foreigners end up owning more of the United States. The issue isn’t any one dishwasher, or one bank transfer, or one asset sale. The issue is what happens when the flow becomes a flood — and that doesn’t show up in the mechanics of the first $600. It shows up in the vulnerabilities that emerge after the first $6 trillion.

NIIP and tuck

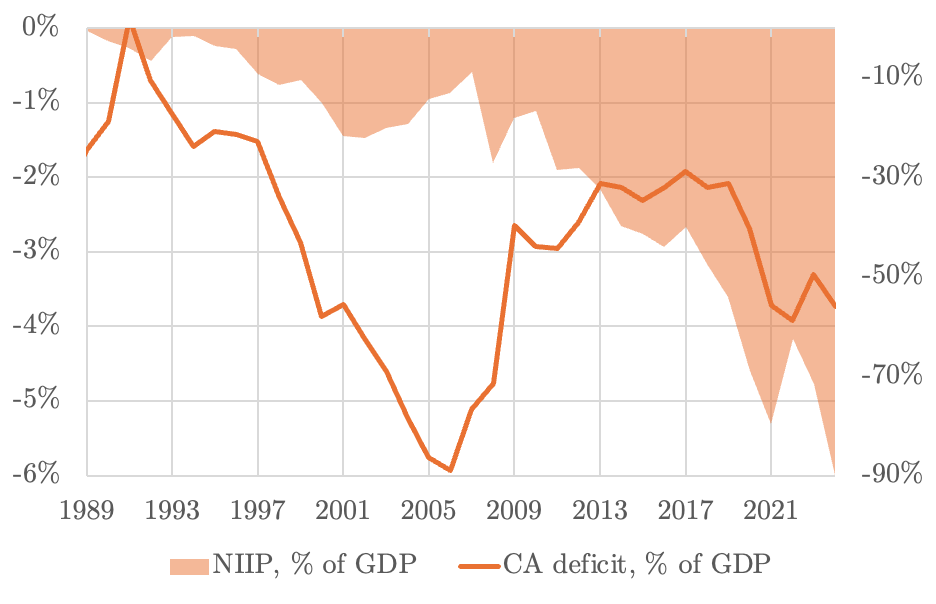

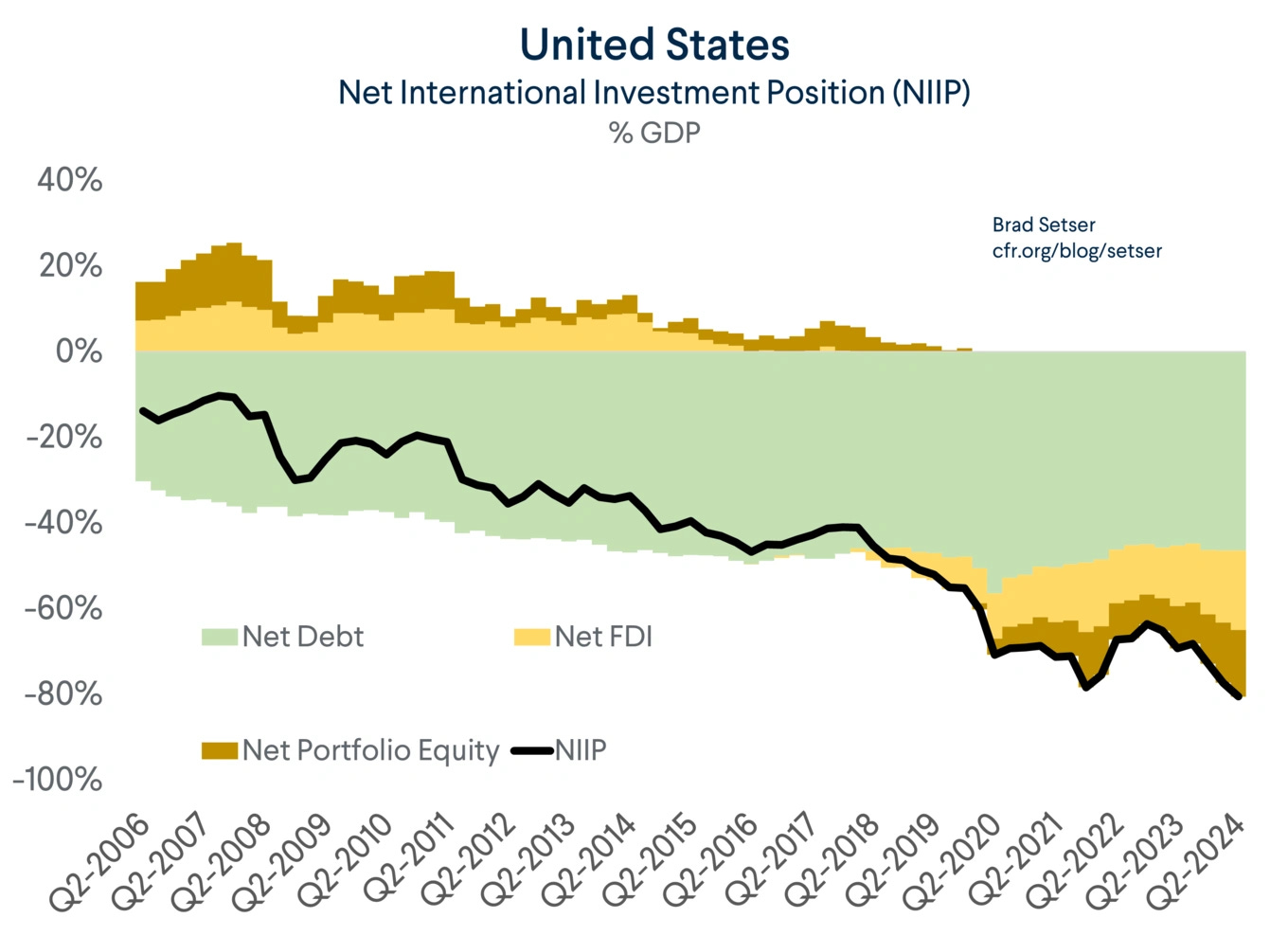

After decades of current account deficits, the U.S. net international investment position (NIIP) is looking pretty negative. What could go wrong?

(I am going to ignore here that a lot of the current account deficit—and by extension, the NIIP—is an artifact of corporate tax avoidance. That’s a subject for another post.)

The obvious thing that could go wrong is that foreigners no longer want to hold dollars. They sell those dollars on markets driving down the exchange rate. As a result, import prices go up and Americans become poorer.

Of course, that would be only foreigners doing to us what we’re doing to ourselves with tariffs. But it is a potential bad outcome.

Let’s think of another one. Foreigners could sell the bonds they own. That would drive down the price of bonds and conversely drive up interest rates for Americans. As a practical matter, most foreigners have parked their claims on the United States in the form of federal government bond issues rather than deposits in U.S. banks.

The problem with that scenario is that it assumes that the American central bank would just sit around and do nothing if interest rates suddenly started spiking. It wouldn’t. Rather, it would print up dollars and use those dollars to buy American government bonds until interest rates hit whatever target the central bank thought prudent.

That would risk inflation. It would also risk a fall in the dollar, which could drive up import prices, and further increase the risk of inflation. But the risk is inflation—the Fed could likely prevent a sudden spike in interest rates and forestall any risk of a government default.

The United States has a lot of reasons to fear future inflation — the negative NIIP is only one of them. Still, it is a reason to try to cut the current account deficit now. But there is a difference between correcting global imbalances and responding to targeted distortion—whether sweeping tariffs imposed on every country are a sensible way to do that is left as a subject for other authors. Or maybe a future post, but right now the ones I read seem to be covering that issue fairly well.

Forced savings and its discontents

There is one other potential bad effect from a persistent current account deficit, but it’s controversial. I’m only going to describe it rather than give it the deep dive it deserves.

A current account deficit basically means that the U.S. is buying more from the rest of the world than it is selling to it. (In our example, that would immediately show up as an increase in foreign-owned deposits in U.S. banks. In the real world, most of those deposits have been recycled into ownership of U.S. treasuries.) However, the converse also has to be true—for the U.S. to buy more than it sells, somebody else has to be selling more than they buy.

That somebody else is the People’s Republic of China. The PRC runs policies that artificially bump up its savings, primarily by forcing companies to retain most of their earnings and doing everything possible to keep salaries low. (Salaries in China have risen by a lot, but the argument is that they would have risen even more if Beijing didn’t put its finger on the market scales.) This is the argument from the book Trade Wars are Class Wars, by Matthew Klein and Michael Pettis.

If you buy that argument, then the trade deficit becomes pernicious. Let’s go back to our early example, but swap out a Turkish company for a Chinese one. In this view, that Chinese company isn’t choosing to keep its money in the United States instead of buying American stuff because it makes business sense. Rather, it’s doing so because Chinese policies incentivize (or even force) it to do so. And by forcing it to do so, Chinese policies are strangling American companies that would have otherwise exported their wares. (The exact mechanisms here get complicated but that’s the general idea.) Even now, they would be impeding reindustrialization in the United States (and elsewhere).

If you believe that is happening, then trade deficits are very bad. Even at the micro level, they’re bad. So the question is whether that is happening.

If it is, however, then the remedy presumably involves targeting China, not the rest of the planet. (Noahopinion has some useful thoughts on this topic.)

Summation

In and of itself, at the micro level, a trade deficit is as simple as buying something from a foreigner and having them hang on to the cash. At the macro level, however, it means either increasing indebtedness to foreigners or increasing foreign ownership of American assets. In the U.S., it’s mostly meant increasing indebtedness. Most of the risks from that indebtedness are exaggerated and boil down to an increased risk of inflation — which is exactly what most attempts to unwind the deficits by policy would also provoke!

But it is possible, if the deficits are the result of malign foreign policy, that the deficits have deindustrialized the United States more than would have otherwise occurred. And if that is true, then we’re playing a different game … and it would make sense to play that game right.

But “playing that game right” is an easy thing to say and a hard thing to figure out. All I can say is that big blanket across-the-board tariffs that scale with the proportional size of individual countries’ trade balances with the U.S. do not seem to be the way to win that game.