Tactical nuclear weapons and the Russo-Ukrainian War

Vladimir Putin will need to go big or get pushed back home

Will Putin use tactical nuclear weapons? That’s a broad question. Let’s narrow it a bit. What would Putin gain from using nuclear weapons on the battlefield?

TLDR: If he used just a few weapons, he would gain no battlefield advantages. But if he used a lot, he would! It could win him the war. The problem for Russia is that Putin’s modus operandi has been to procrastinate and avoid tough decisions. Since the only effective way to use tactical nuclear weapons is to use them in large numbers, then I do not think that he will use them any more effectively than he has used any other weapons at his disposal. But I do think if confronted with defeat he will choose to deploy a few in order to draw the United States or NATO into the war, because he will lose less face if beaten directly by the evil West than he will lose if he is seen to have been defeated by the Ukrainian armed forces alone.

Tactical nuclear weapons, as the name implies, are intended to be used on the battlefield against enemy troops formations. During the Cold War, NATO fully intended to use them against the Soviets, which is why I heard the following terrible joke from an older sergeant while drilling outside Kaiserslautern long after the Cold War ended:

Q: What’s the average distance between two German towns?

A: About two kilotons!

(Yes we were smoking dried plants in rolled paper. That’s what we did on drill in the best damn Army on the planet.)

The thing is, the joke is wrong! German towns are more than two kilotons apart — tactical nuclear weapons aren’t that destructive and they don’t magically disintegrate opposing forces. Moreover, enemy forces can react to their deployment by dispersing, shrinking supply dumps, and digging in. In other words, you can change the course of a conflict by using them, but you have to use a lot, and it isn’t clear that they are easier or more cost effective than dumping a boatload of conventional munitions on enemy heads or employing accurate precision weaponry.

How do we know this? Well, the U.S. Army spent a lot of time and money trying to figure out how it could use atomic bombs on the battlefield. In the 1950s, the Army reorganized itself around the “Pentomic” structure (don’t ask what that was supposed to mean) and planned to fight a Soviet invasion with tactical nuclear weapons, some small enough to be launched by infantry squads. In 1963, the Army Combat Development Command commissioned a two-year exercise called Oregon Trail to figure out exactly how they would use these things in combat.1

In Oregon Trail, the average number of casualties came to about 100 people per tactical nuclear strike on fixed enemy formations.2 And targeting proved to be much harder than anticipated. In the Florida Island sub-exercise, eight consecutive aerial reconnaissance missions missed an entire infantry company, an artillery battery in firing position, a tank company in an assembly area, a command post, and ten deuce-and-a-halfs lined up in a row. More generally, planes picked up only 31 percent of their potential targets.

Now this was using 1963-65 technology. And the Florida Island exercise took place in more forested terrain than most of southeastern Ukraine. But we do have the performance record of the Russian Air Force (VKS). When the VKS dives below the clouds to acquire targets their planes get shot down; when it stays above it has trouble finding targets. And it can’t plan a grocery list. So I doubt they would do any better than the USAF could do back in ‘65.

Even if you find the enemy, they get a vote—they can dig in and disperse, rendering nuclear weapons much less effective. Take for example NATO Exercise Fox Paw in 1955. Forward units and aerial support identified 20 enemy formations that escaped because they dispersed between being identified and being fired upon.

The upshot is that even though tactical nuclear weapons make big bangs, you have to use a lot of them. In 1958 and 1963, the U.S. staged two war games. The 1958 game simulated a conventional invasion of South Vietnam by NVA forces; the ‘63 game simulated a Chinese invasion of Laos and Thailand. The first scenario required the use of 34 tactical nuclear weapons in order to repel the North Vietnamese. The second required the use of 208 weapons to … well, the game ended before the ultimate outcome was determined. These results paralleled a 1955 NATO exercise called Carte Blanche in which 300 tactical nuclear weapons were deployed in the first two days of play without stopping the Soviet advance — although to be fair, that exercise assumed that the Soviets would respond in kind.

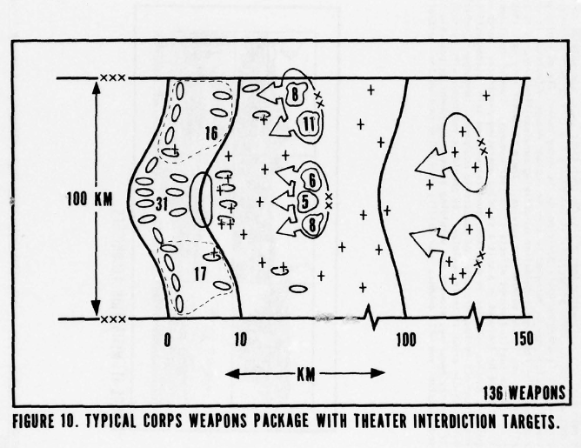

Things were about the same in 1977, when the Army published “Nuclear Notes,” a series of training primers on nuclear weapons. (SGTNVM thanks you for the reference, MAJJKR!) In Note Number Six, the authors laid out how an Army Corps would defend itself against seven divisions bearing down on it: three in contact, two on “high speed” approach, and two forming up in the rear. Plans called for dumping 136 warheads on them within two hours, delivered by artillery, missile, and aircraft. 102 warheads would (try to) disrupt enemy formation while an additional 34 would — targeting gods willing — strike rear airfields, bridges, and supply dumps. And even then the wargames suggested that success was not guaranteed … although to be fair in real life the odds would probably be pretty good.3

What about attacking supply lines and ammunition dumps? Couldn’t tactical nuclear weapons be an excellent way to do that? Again, the answer is that they will work only if used in massive numbers. A RAND targeting study from 1965 calculated that one tactical nuclear weapon was the equivalent of 12 conventional sorties. Nowadays that ratio is more likely one-to-one, since precision weapons can crater runways and hit depots with accuracy.

Now in 2022 the VKS appears to lack precision weapons and the ability to conduct coordinated air suppression campaigns, which would make nuclear weapons look attractive. But given that roads and rails are easily repaired and considering the results of Cold War exercises, the Russians would need to use hundreds of weapons on rail heads and airfields and supply depots to disrupt the supplies flowing to a Ukrainian offensive.

Did anyone figure out a use for tactical nuclear weapons that didn’t involve firing off hundreds of bombs at an invading force? Why yes! The Royal Netherlands Army possessed tactical nuclear weapons lent by the Americans. Dutch doctrine was to use them to defend river crossings, where Soviet troops would have to concentrate and regroup. The shaded areas are where the Royal Dutch Army would nuke the Soviet Bloc invaders trying to cross the Elbe, falling back to the Weser River to do it all again should they fail the first time.

Even with the river crossing strategy the Dutch faced two problems: first, if the Russians and East Germans managed to get across the Dutch would still have to use a lot of weapons since the Communist forces would immediately disperse.

Second, safety was a bitch. It often took over an hour just to ensure that friendly units were out of the way. And in exercises the Koninklijke Landmacht often screwed up. In 1959, they loaded 17 kiloton warheads instead of a 2 kiloton devices. (Whoops!) In 1966, they launched nuclear strikes on their own forces. The next year, four Dutch divisions marched directly across areas they had just attacked. (Radiation fears are greatly overstated but this is a really bad idea.) Dutch commanders vacillated between restricting attacks to fixed targets, which wasn’t useful, and tolerating terrible mistakes, which wasn’t palatable.

In short, for Putin to get anything out of tactical nuclear weapons, he will need to use a lot, which means calling them up en masse, which means that Western intelligence services will know all about it beforehand. Moreover, the Royal Dutch Army was (and is) one of the best-trained armies on the planet and it had trouble deploying them— how do you think the 21st-century Russian army is going to do?

Alternatively, the Russians could fall back to rivers and deploy relatively small numbers of nuclear weapons to defend their lines. But again, they would have to start falling back now while bringing the nuclear weapons into position.

Putin is not taking such decisions. Rather, he is procrastinating, as he has for the entire war. If he decides to use tactical nuclear weapons without taking the steps needed to rain down hundreds at a time, all he will do is bring down on himself a world of hurt for no tactical, operational, or strategic gain.

But maybe bringing down a world of hurt would be the point? Putin could invite Western intervention by attacking NATO territory, of course, but that could risk uncontrollable escalation! Using one or two (or ten or twenty) nuclear weapons in Ukraine is a safer bet. The U.S. will likely respond conventionally, and only in Ukraine, and that could let Putin claim that it was the United States what intervened and defeated him without risking actual defeat. He could then go home having been beaten by a peer enemy, rather than having been crushed by a bunch of Ukrainians that he has claiming are just wannabe Russians with a funny accent.

But if his intention is to win rather than provoke an “honorable defeat,” then Putin will have to go big.

If something similar was commissioned under Eisenhower, I haven’t been able to find it. Oregon Trail — or as I would have had to write it when I was in the Army, OREGON TRAIL — is still classified but parts appear in secondary sources. One scenario involved a U.S. attempt to retake Taiwan after a successful Chinese invasion was handwaved into existence. The exercises were crazy detailed: it took the planners three months to play out a 72-hour operation.

Dyson, Gomer, Weinberg, and Wright, “Tactical Nuclear Weapons in South East Asia,” Study S-226 (Institute for Defense Analyses, Jason Division: March 1967), pp. 9-10.

Digression: Note Number Nine looks a lot like what we practiced for a few unpleasant days at Fort Benning.

I tend to agree that there’s very little that Putin could accomplish in any strictly military sense by going nuclear, which is why I haven’t worried about it too much. But war is ultimately politics by other means, right? Given what I think his political goals are, using a small number, maybe even one, starts to make sense.

Regardless of whether he managed his maximal or minimal territorial goals in Ukraine, NATO needed (and needs) to be dealt with. It wasn’t going to sit there and ignore the situation. Either it collapses after being shown to be an ineffectual paper tiger, or it is neutralized by political or military considerations.

I think escalating to the nuclear level potentially gets him neutralization, albeit not in ideal fashion. I personally don’t believe that escalation would inevitably go to the strategic level, but I suspect (based in part on what some mutuals have said) that a lot of Europeans will become very concentrated on the possibility. Since NATO troops aren’t (yet) directly involved, I think the natural reaction will tend towards “freezing” the conflict.

That’s about as good as Putin can hope for right now. He’d be happy to kick off Cold War 2 with some gains in Ukraine. That lets him crush any remaining domestic opposition while boxing out western cultural and political influence as much as possible.

I think the best counter is a strong commitment to massive (and fast) conventional retaliation, up to and including facilitating Ukrainian advances back into their territory. It might still be worth it to him to be able to say he was beaten by the US, a possibility you note, but ending the war in a far worse position on the ground than Russia started leaves him at risk domestically.

Excellent post.