Emergency substack 2: The Ontario electricity export tax won’t hurt Americans

Market structures mean that the burden would fall on Ontario

“Life moves pretty fast. If you don't stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.” —Ferris Bueller

NEWSFLASH

Right before I hit “send,” Doug Ford abashedly announces that he’s lifting the export tax. Oy vey. Well, here it is anyway, with a new conclusion.

The Old Intro

Ferris Bueller captured how I feel about the trade war. Things keep happening in fields that I know a little about. The press and Twitter (“X,” whatever) make claims that are wrong. And I feel obligated to stop and look around and correct the misapprehension instead of doing all the other things that I am supposed to be doing.

Premier Doug Ford of Ontario just imposed a C$10 per MWh ($6.90 U.S.) export surcharge on Ontarian electricity exports. Given market structures, this will have next to zero effect on American consumers. It will be paid by Ontarian exporters. Let me repeat that. IT WILL MOSTLY BE PAID BY ONTARIAN EXPORTERS.

Why?

Ontarian exports sell the vast majority of their exports on American wholesale markets. These sales are opportunistic — when a price gap opens up between Ontario and neighboring markets, Ontarian producers export their excess production. These exports, however, are too small to have a big impact on American prices. American prices may rise a little, since the cost of one of their supply sources went up, but most of that increase in costs will be eaten by the producers.

The upshot is that Ontarian producer will sell at whatever the American market price happens to be, pay C$10 to the Ontario government, and stop. The export tax did, however, irritate President Trump and lead him to hike tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminum from 25% to 50%. He then reiterated his calls to make Canada the 51st state:

The only thing that makes sense is for Canada to become our cherished Fifty First state. This would make all tariffs, and everything else, totally disappear. Canadians’ taxes will be very substantially reduced, they will be more secure, militarily and otherwise, than ever before, there would no longer be a northern border problem, and the greates and most powerful nation in the world be bigger, better and stronger than ever. The artificial line of separation drawn many years ago will finally disappear, and we have the safest and most beautiful Nation anywhere in the world—and your brilliant anthem, “O Canada,” will continue to play, but now representing a GREAT and POWERFUL state within the greatest Nation that the world has ever seen!

All that for a measure that will hurt Americans very little, if at all.

Deeper dive below.

Electricity markets

North America is broken up into several different electricity markets, called ISOs, for “independent systems operator.”

Among other responsibilities, the ISO runs a wholesale market for electricity. Generators (or, increasingly, the owners of electricity storage operations) bid into the market in increments between 5 minutes and one hour, depending on the market. Essentially, they call up the ISO and say, “Hey, if the price of electricity between 12:00pm and 1:00pm is above $X, then we promise to pump in Y megawatts of electricity over that period.

At the same, buyers are doing the same thing, submitting bids that say, “When the price of electricity falls below $Z, then we promise to consume (and pay for) A megawatt-hours over the period.”

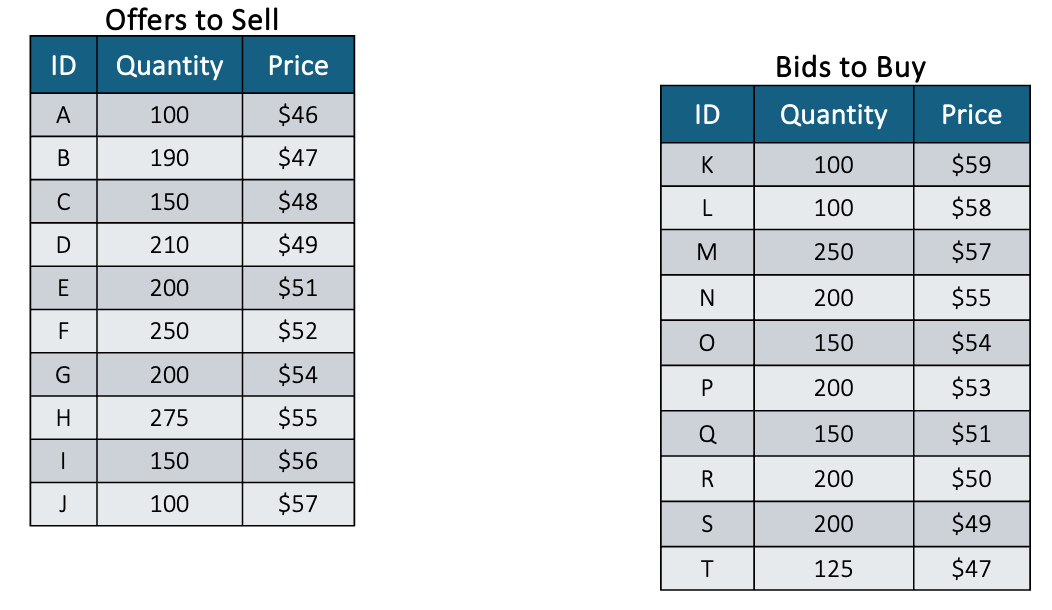

So the ISO gets two schedules from a bunch of sellers and a bunch of buyers that look like the below example that I pulled out of my class lecture notes. I randomly assigned numbers; they were not cooked up for this blog post.

Here, seller A promises to sell 100 MWh (during the stated time period) as soon as the price goes above $46 per MWh, but seller G won’t feed anything into the grid until the price hits $54. Likewise, buyer K will buy 100 MWh at any price below $59, whereas that known cheapskate, buyer R, won’t play until the price falls to $50.1

The ISO aggregates all these bids and asks comes up with a price at which the market (more-or-less) clears:

The market for electricity generated between noon and 1pm clears at a price of $52, although seller F was willing to sell a bit more than she was able to.

So what about taxes? Well, the first thing to note is that if the tax is less than the difference between the generator’s marginal cost and the market-clearing price, then nothing will happen to prices. In the above example, that means if Canadian generators produce for less than $42 per MWh, then the price won’t be affected. The order of sell offers will change, but the Canadians will still be willing to sell for less than $52.

Since Ontario produces a lot of hydropower, with a marginal cost of zero, this is certainly the case. On the other hand, Ontarian producers could always decide to sell at home. So they won’t offer for less than what they can make on the Ontario market.

That means we should look at a case where the tax really is enough to make Ontarian producers decide not to sell in the USA.

Let’s say now say that Seller A (in pink) is the lowest-cost Canadian generator. She has 10% of the market before the taxes hit. Now she has to pay the Province of Ontario $10 on every MWh sold in America. Well, her cost has now jumped from $46 per MWh to $56 per MWh, and we can rearrange the schedules as follows:

Neither the price nor the quantity has changed, even though the Canadians are no longer selling into the American market.

Note that this heuristic example doesn’t do a bad job of capturing the actual situation. In the New York market, for example, the share of Ontarian exports in total consumption has averaged around 4% in this century, with occasional spikes.2

Still, the above shows only monthly data. There might be times when Canada is supplying most of the power being sold on the wholesale market. (On average, about one-third of power is actually outside the wholesale market under fixed-price contracts called “power purchase agreements,” abbreviated PPA. More on that in the next section.)

What happens if the export tax takes a bunch of Canadian producers off-line at a bad time, when they make up a large chunk of supply?

The price has gone from $52 to $54. That’s an increase, yes … but the tax was $10. Only one fifth of it was passed on to American consumers. (Technically, in this case, none of it was passed on — the price rose because the Canadians chose not to sell in the American market.) But to get that we had to assume improbably high costs and improbably large market shares for Canadian generators.

In other words, even had Premier Ford stuck to his guns, the tax would not have had a big effect on wholesale prices.

Is there another way that the taxes could have been passed on to Americans?

Export taxes and cross-border Power Purchase Agreements

Maybe. But probably not.

Two entities dominate the Ontarian export electricity market. The first is Ontario Power Generation (OPG), a behemoth owned by the provincial government. It generates more than half of Ontario’s power. The second is Brookfield Renewable Partners, which operates several hydroelectric facilities and a slew of wind farms. The remainder of the market is divvied up among a slew of smaller producers, the largest of which is H2O Power FirstLight Power.3

Inasmuch as these entities sell into American wholesale markets, Canadian attempts to impose export taxes on them will not have a big effect on American consumers. Rather, that electricity will be sold at home, driving down prices in Ontario.

Now, there is one way that these big players could pass on the tax to American consumers. If they sold power not on the wholesale market—where prices vary—but via a direct contract, then they might be able to pass on the tax. Direct electricity contracts are usually called “power purchase agreements” (PPA) and they often have built in change-of-law clauses (p. 121), which let one party or both alter the contract should the government change laws in a way that raises costs. Brookfield Partners signs a lot of PPAs. Ontario Power Generation, however, does not appear to do so.4

In other words, the largest single exporter does not use the only contractual arrangement that could lead to Americans paying a majority of the export tax.

Conclusion

Well, Premier Ford backed down, so I pretty much wrote this for nothing. But it was a dumb way to try to retaliate against the Trump Administration. In fact, Premier Ford was more “Trumpian” than Trump!

Announce a bad-sounding measure that won’t hurt your opponent;

Realize that it will hurt you more;

Declare victory and repeal the measure.

When Ford carried out step (3), he said it due to a “very good discussion” with Commerce Secretary Lutnick and not because President Trump threatened to take high tariffs up to the stratosphere. It seems to be working out for the Premier — he still looks tough to Canadians, and now President Trump has called him “a very strong man.”

So politically the whole thing seems to have worked out!

But economically, it was a dumb idea. And I don’t mean dumb in the standard “free trade is good yadda yadda” sense of dumb, I mean dumb in the “this won’t hurt your opponent” sense of dumb.

And I suspect the politics would have played out differently had decision-makers and the public realized that.

There is no reason why these sellers or buyers need to be separate entities, of course. The same seller can say, “I’ll sell 50 MWh at $51, and an additional 50 MWh if it hits $52, and 25 more MWh if it goes to $53,” and so on. This also applies to buyers.

This footnote is a self-referential digression so feel free to ignore it. I am old enough to find it odd to use “this century” to refer to the 21st. I am also old enough to say that despite the giant shock of 9-11, the 20th century didn’t really seem to end until sometime between 2008 and 2016, when I realized that I could no longer fully participate in modern life without a smartphone. That realization hit me in 2016, at Yankee Stadium, when they stopped using paper tickets, but it had been building for some time.

On page 20 of the OPG annual report, they note that “OPG’s generating facilities in the US are either subject to power purchase agreements (PPAs) for the supply of energy and capacity into the respective markets, or receive wholesale market prices.” But when they refer to cross-border sales, they say only: “OPG also sells into, and purchases from, interconnected electricity markets in other Canadian provinces and the northeast and mid-west regions of the United States. Under these arrangements, OPG’s performance obligation is to either physically supply energy, settle financially, or provide capacity.” That is basically a description of the various ways one can participate in a wholesale market!