An Immodest Proposal

The only thing more absurd than U.S. policy in Panama ... no, current U.S. policy couldn’t get more absurd in Panama. Why not just annex the whole thing?

When then President-elect Trump first raised the Panama Canal issue, I wasn’t surprised. Cheniere, the company that handles half of America’s natural gas exports, is also the single largest donor to Republican candidates in the hydrocarbon industry. And I know people who know people at Cheniere, who told me that their executives were annoyed at the high fees and long wait times at the Panama Canal. Not that you needed inside information to know that: Cheniere’s complaints were out in the open.

So I thought I knew how this would play out. I was wrong.

President Trump kept escalating his claims on the Canal. Panama went out of its way to eject the Chinese from their port concessions. And then the Secretary of Defense visited Panama.1 He proceeded to humiliate President Mulino by insisting on military basing rights and unilaterally deleting a line about Panama’s sovereignty from the agreement. And now we have a demand that Panama immediately eliminate charges on U.S. Navy ships using the Canal — while at the same time pursuing a policy towards LNG tankers that punches American LNG exporters in the nose.2

In the words of Will Freeman from the Council on Foreign Relations, “It makes me second guess how much the LNG companies are driving all this versus that the President just wakes up thinking about Panama a lot.”

Self-Cornering Foreign Policy

Hegseth’s Top Gun diplomacy left Washington in a bind. The administration has raised expectations that something will be done about the Canal. Having accused Panama of handing the Canal to China — a palpably false claim that apparently 23% of Panamanians believe — the Trump Administration can hardly back down without looking weak. But short of reoccupying the former Canal Zone by force, it’s not clear what “taking it back” would actually entail. A scattered set of near useless military bases?3 It is far from certain that the Administration will be able to get even that, given that American basing rights are a violation of the Neutrality Treaty.4

If you can’t credibly seize the Canal, and you can’t admit you were bluffing, then you need a third option. It will have to deliver control of the Canal and signal American strength, but also give the Panamanians enough to get them to agree.

So could the situation get more absurd?

No, no it could not. Trying to annex all of Panama would be less absurd than the bind we’ve backed ourselves into.

Taking all of Panama would be less contradictory and more likely to “succeed” than whatever it is that Washington is trying to do right now. At least that would be something that the Panamanians might be likely to accept. Hell, it would be the only way I can think of to legitimize “taking back” control of the Panama Canal.

Once you’ve broken the Neutrality Treaty, what is the point in stopping halfway?

Don’t take the Panama Canal, take Panama. Make it a U.S. territory. Guarantee Social Security, extend the Earned Income Tax Credit, build out the highways, Americanize the health system, federalize the budget. Offer the Panamanian people not “partnership,” whatever that means, but citizenship.

What follows is not a serious proposal. In fact, it’s completely unserious and not going to happen. But I am going to treat the idea Very Serious™ and walk through the implications. Many will seem ridiculous — but they’re far less ridiculous than trying to reoccupy the Canal Zone or continuously humiliating one of the most pro-American governments and pro-American populations on the planet.

Accession mechanisms

Assuming absurdity becomes policy, how would it work? You need Congress to admit a territory. Even the Trump administration would hesitate to try to annex Panama without Congress.5 Even in the case of American Samoa (where Congress didn’t ratify the 1900 cession by the Samoan high chiefs until 1929) the annexation was based on the Senate-ratified Tripartite Convention of 1899 in which the U.K. transferred its formal claims to the U.S.6

The most relevant precedent would be the negotiations over the Northern Marianas Islands (CNMI). As the U.S. moved to grant de jure independence to the islands seized from Japan at the end of WW2 (and return Okinawa to Japan) popular opinion in the Northern Marianas swung strongly towards remaining in a “political union” with the United States. The result was a 1976 document called the Covenant, which granted citizenship to the people of the northern Marianas and extended the Social Security system. It did not, however, make the islands fully subject to the trade and immigration laws — that would be the subject for future negotiations. In addition, the CNMI government was allowed to violate the principle of one-person one-vote in designing its legislature and limit land ownership to native Chamorros.7

Congress later extended many federal transfer programs to the islands, mostly as block grants. The medical system has been partially integrated into Medicaid, but CNMI medical licensing remains distinct, and not all CNMI doctors can practice in the rest of the United States.

In other words, the Trump Administration could make Panama an offer as long as they got a Congressional majority on board.

Federal transfers

Of course, political accession is only half the battle. The real adjustment would be economic — keep in mind, Panama is poor. Sure, it’s grown like gangbusters over the last two decades. But it is poor. The median household income is $9,970 per year. For comparison, the poverty line in Puerto Rico (until 2023) was around $11,300 for a family of four. Only one-fifth of Puerto Rican households earn less than the median family income in Panama.

So the transition would be rocky. Let’s take each sector in turn.

(1) Medical care

The Panamanian government currently provides health care in two ways. The first is the Social Security Fund (CSS, for Caja de Seguro Social). It provides some health care coverage to formal-sector employees and their dependents, covering more-or-less 75% of the population, although some estimate that only half the population actually receives medical benefits. (See page 20.)8 In addition, the Ministry of Health (Minsa) operates free-to-all hospitals and clinics.

Congress would have to authorize a Medicaid Section 1902(j) waiver for the Commonwealth of Panama, just as it did for the CNMI. Panama could then use its own local eligibility criteria and license its own health-care providers. Existing CSS doctors and Minsa facilities would qualify as federally reimbursed providers.

What would this cost?

To participate in U.S. Medicaid, Panama would need to implement a billing infrastructure compatible with federal claims and audit systems, including the Medicaid Management Information System (MMIS). A 2019 GAO report estimated the cost of creating Medicaid-compliant systems.9 Under current law, the federal government would reimburse 90% of this cost, but for a new territory that would almost certainly have to be 100%. Call it $600 million.10

Congress would then vote a block grant to finance Panama’s new program. The cost of care for existing CSS and Minsa patients would be taken over by the federal government. Universal services, such as vaccination drives and prenatal health care would not be included. Some CSS and Minsa facilities would likely need upgrades to meet U.S. federal health and safety standards, although these costs would be modest compared to the overall transfer burden, perhaps $200–$500 million spread over a decade.

The Panamanian government currently spends about $6 billion on health care. Roughly $800 million of Minsa spending would be eligible for federal support (data on p. 23).11 CSS spent $4.9 billion.12 Congress would finance about 55% of CSS using Guam and the CNMI as models. In practice, Congress routinely overrides those caps and funds Medicaid in the territories entirely through federal appropriations. Puerto Rico’s reimbursement rate, for example, is officially 76% but emergency appropriations often push it up 100%.13

Puerto Rico currently gets a block grant around $3.7 billion, around $2,400 per recipient. If we federalized half of CSS and added $800 million for Minsa, that would come to about $3.3 billion, roughly $1,000 per recipient, 40% of the level in Puerto Rico. That is not far off the $1,500 that Panama spends per person on health care.

Call it an up-front cost of $600 million followed by a recurrent expenditure of $3.3 billion. Although federal rules would push gradual convergence in health care costs, the CNMI shows that Panama could maintain a parallel medical system for a rather long period of time.

(2) Other transfers

Congress would not have to extend anything to Panama. But it likely would. In 1982, for example, it extended a version of the program usually known as “Food Stamps” to the CNMI called the Nutrition Assistance Program (NAP). Congress finances this via a block grant.

CNMI eligibility rules vary by the size of the block grant. In 2021, the income limit for a family of four was $26,208 — under that rule, pretty much the entire population of Panama would qualify. Congress won’t pay for that; Puerto Rico before Hurricane Maria is a better example. The maximum income limit for a family of three was $7,200, which would cover roughly half the Panamanian population.

Panama could use the CNMI formula, capping household food costs at 27% of income. The value of the “canasta básica” in Panama was $301 per month in February 2025. Combine that with Panamanian incomes and the total cost of the program would come to about $1.4 billion per year and cover about 60% of the population.14

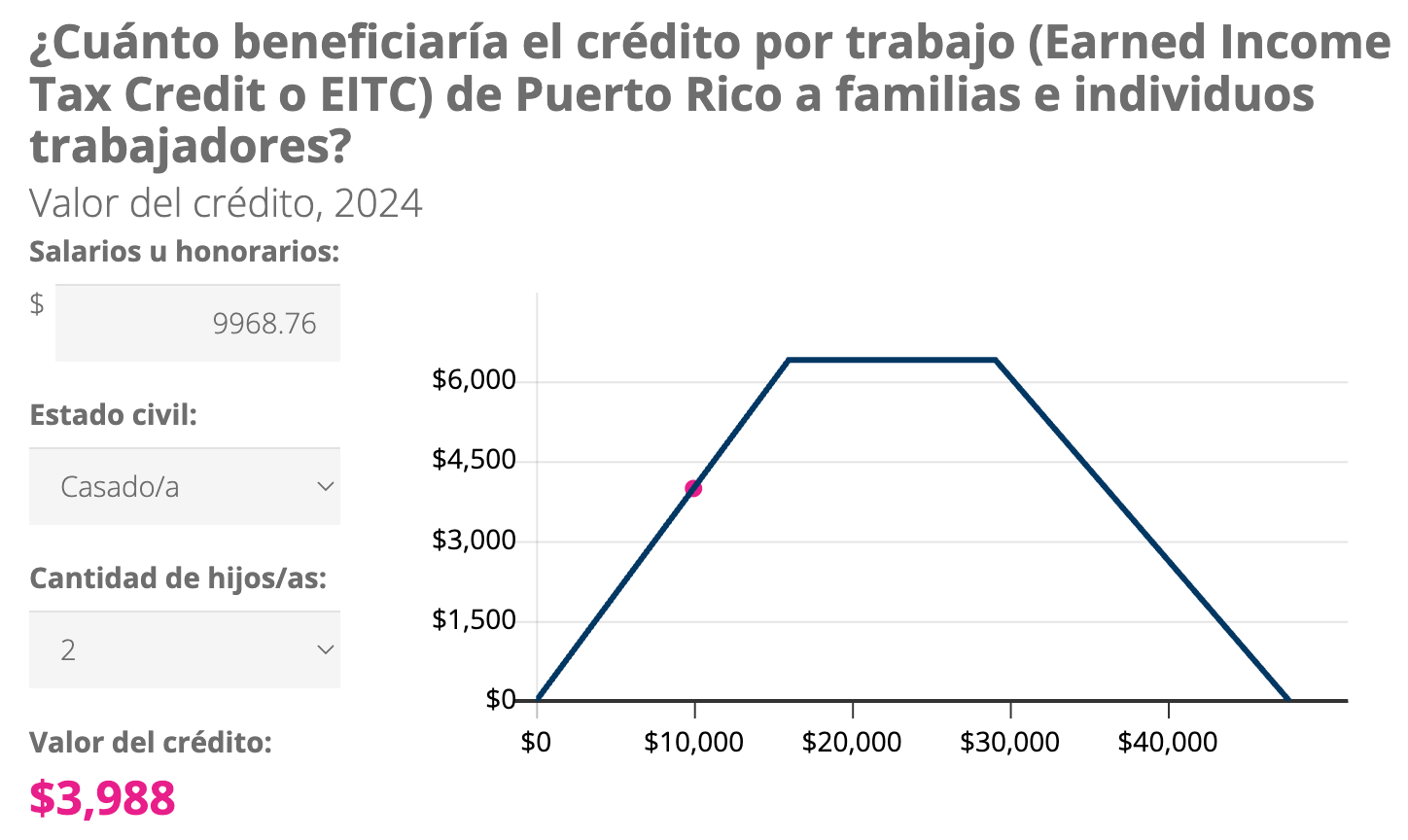

In addition, Congress could make Panamanians eligible for the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). The EITC is a form of negative income tax. If you have no earnings, you cannot collect it. As your earning rise, so does the subsidy, until it phases out at a certain level. Congress did not extend the benefit to Puerto Ricans until the passage of the American Rescue Plan in ‘22.

Extending it to Panama (using the current Puerto Rican benefit formula) would cost $3 billion per year if the federal government picked up the entire tab. That is rather more generous than the Puerto Rican program, which caps the federal contribution at $600 million in 2021 dollars, adjusted for inflation, with the rest financed from the Commonwealth’s own revenues. Let’s say Congress pays the whole thing to sweeten the Panamanian deal.

What Congress does depends on two things. How attractive do they want the offer to be? How worried are they that the massive influx of cash will distort the Panamanian economy?

(3) Other spending

The United States would have to start up a federal court system, create federal offices, send law enforcement agents to the Isthmus, and probably start building roads and other infrastructure. How much would that cost?

Federal nondefense spending on wages and procurement in Puerto Rico came to about $1.1 billion in 2023.15 Panama would be about the same. Federal education programs would also begin to flow to Panama — including Title I funding for schools serving low-income children, special education grants under IDEA, and Pell Grants for college students — although total education aid would likely remain well below $1 billion annually. So let’s add another billion to the estimate and call it a day.16

I have deliberately not included defense spending, since the Trump administration appears to want to increase how much we spend in Panama! Defense spending in Panama is a benefit, not a cost.

Over time, of course, spending will rise as Panamanians began to collect Social Security, Medicare, and veterans’ benefits. But that would take time. And as we will discuss in the next section, federal revenues from Panama will also rise.

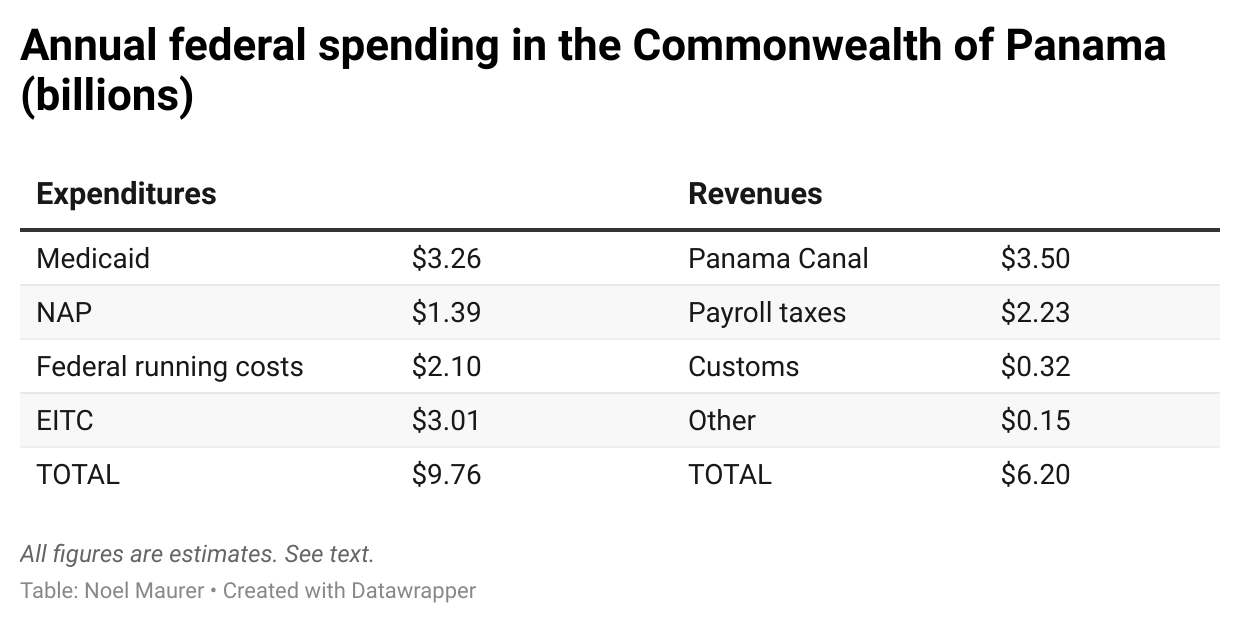

(4) Federal revenues

The federal government would claim the Canal’s $3.5 billion net income. Isn’t that the whole point?

(Yes, I am ignoring the fact that the Panamanians doubled the size of the Panama Canal on their own.)

We would also start collecting Social Security taxes. A decent ballpark estimate would be about $2.2 billion.17 Now, in practice this would be messy. About 60% of current CSS payroll tax revenue (along with some of the associated spending) would also have to be transferred to the Social Security Administration. But that can be sorted out.

Now add another about $320 million in customs revenue and maybe $250 million in other revenues and add it all up:

In that world, you take back the Canal with no security issues and (assuming you win a referendum in Panama) for the low low cost of $3½ billion per year. That’s about $10 per mainland resident. Another billion or three either way won’t make a big difference.

Labor market adjustments

Fiscal costs are just the beginning. The real shock would hit Panama’s labor markets.

The median wage in Panama is about $8,820 per year. Assuming a 2000 hour work year, that’s an hourly wage of $4.40.18 In other words, most of the Panamanian labor force earns less than the current federal minimum wage … although keep in mind that the World Bank estimates that the cost of living is about half what it is on the mainland.

Given low Panamanian incomes, Congress would presumably not choose to extend U.S. minimum wages to Panama. (There was a reason it took forty years to get around to extending them to Puerto Rico, and then eight more to fully phase it in.)

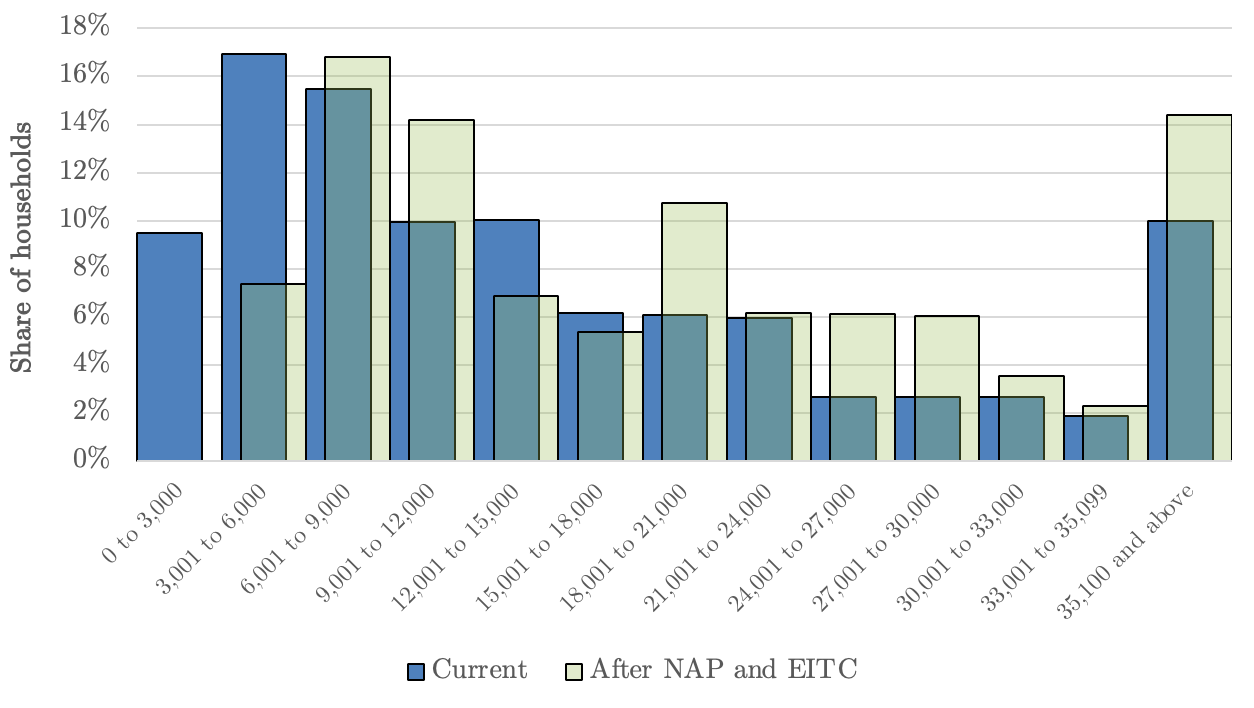

Nonetheless, NAP and the EITC will shift Panama’s entire income distribution significantly upwards. (See the below figure.) For the poorest tenth of Panamanians, NAP will raise family incomes from around $1,600 per year to roughly $4,800. Median family income would rise from $11,500 to $12,400.19 A very large chunk of people are going to decide not to work — two-income households will become one-income, children will stay in school longer, people will retire early.

The EITC will have an even bigger impact on incomes. By itself, the EITC would raise the average income of the bottom tenth to only $2,300, but median incomes would soar from $11,500 to almost $18,000. Add NAP back in and the average annual income of the bottom tenth rises to $5,400, although median incomes remain $18,000, since NAP benefits would phase out at around $13,000 per year for a family of four but the EITC would remain for incomes as high as $40,000.20

All this federal spending will also have significant impacts on product markets — expect plenty of inflation. You just injected a net $3½ billion per year in purchasing power. Prices is done gonna rise, and nominal wages will rise with them. (Right now you can rent a nice two-bedroom within walking distance of the subway for less than $1,000. That won’t last.) You can also expect a building boom in the suburbs and smaller cities, as people take their federal dollars and use them to upgrade their living conditions.

Still, the inevitable price rises will spark discontent — even if real incomes stay ahead.

Migration

It’s hard to know exactly how many Panamanians would move, but with minimum wage around $30,000 per year in parts of the United States it will still be an attractive proposition for some. Puerto Rican net emigration peaked at 2% a year in the early 1950s before falling to zero by the 1970s. Panama’s population is older now than Puerto Rico’s was then, but the wage gap is bigger.

Even an exodus of 2% per year is only 90,000 people per year. That’s not nothing, but it won’t even be noticed in most of the U.S. Nonetheless, there are only 85,000 Panamanians living in the U.S. right now (along with their 155,000 children of all ages) so they would be set to become a major American ethnic group. Which is great news for both baseball and soccer.

On the Panamanian side an exodus of that magnitude would generate significant labor shortages and cause wages to rise — along with federal spending labor shortages would further fuel inflation on the isthmus, even if wages are likely to rise faster.21

There will be less brain drain than you might think, however. Doctors and lawyers will need to retrain if they want to move to the mainland. Engineers are paid poorly by American standards, but not poorly enough to create a mass exodus. For example, the median electrical engineer working at the Panama Canal Authority makes $77,610. That would put them in the bottom tenth of American electrical engineers (where the median is $118,780), but the cost of living is about half what it is in the States. That will likely change over time as prices rise in Panama, but there won’t be a mass fuga de cerebros.

I wouldn’t be surprised to see a big reverse migration of mainlanders to Panama! There would be tax benefits, like Puerto Rico, but Panama is far more connected to the rest of the world. Panama City is one of the world’s great metropoli and getting greater all the time. (San Juan is many things, but not that.)

What you won’t have to worry about is the southern border of Panama. The Panamanian government has already managed to shut that off. The U.S. won’t have any trouble keeping that closed. If anything, the northern border with Costa Rica is more likely to be a problem. We might need to build a wall.

Various and sundry

The financial system would pose a conundrum. Constitutionally, Panama wouldn’t have to change its financial regulation. Congress easily could carve out an exception, just as it did for immigration and land law in the Marianas. Bank supervision in Panama is fairly strong and the financial system is stable. On the other hand, banks kind of like access to the Federal Reserve and federal deposit insurance — for example, Panama has no deposit insurance scheme.

Panama would have to loosen its bank secrecy laws, but both the country and its individual banks it have been moving in that direction for a while. Federal law of course would override those laws whenever criminal law, national security, or presidential whims (sigh) were in play.

And unlike Puerto Rico, the existing financial cluster means that the Commonwealth of Panama has a sector ready to take advantage of an influx of high-income tax-avoiding Americans. I would bet on the financial cluster growing significantly. Miami saw a recent boom; an American Panama City could draw away a lot of that energy.

Integrating civil law won’t be a problem; the U.S. did that already in Puerto Rico and the Philippines.

Estamos Unidos?

Of course, none of this is going to happen. The cost isn’t prohibitive but it’s also not small. Four billion dollars a year is a lot of money — and that cost will likely rise even if the Panamanian economy continues to grow rapidly.

Before the Trump administration, if somebody had asked me, I would have said that in the extremely unlikely event that the U.S. offered Commonwealth status to Panama, then it would win in a landslide. But now after all the bluster and ill will, now I’m not so sure.

The thing is, offering Panama territorial status is less absurd than the current blundering. It would be quite a bit more respectful of the Panamanian people. The costs to the United States of just going all out and trying to annex the entire Republic of Panama are quite a bit less than the costs of the aimless threats and blundering that we’re currently carrying out.

If we are going to bear the costs of a ridiculous foreign policy, then let’s at least aim big! Something that they will remember in the 22nd Century, assuming the robots don’t replace humanity. Annex Panama.

The link goes to the indispensable Mat Youkee, the Economist’s man in Panama.

I have to be clear: I think that the Administration’s decision to charge special fees on Chinese-built ships is a good idea. The policy is the result of a Section 301 investigation that began under the Biden administration; it did not come out of nowhere. China’s dominance of international shipbuilding is a clear strategic threat to the United States (and Europe!) in a way that South Korea’s or Japan’s is not. That said, the policy’s success depends on both subsidization of American shipbuilding and active coordination with yards in South Korea, Japan, and the Philippines to build what America needs during a long ramp-up.

The Trump Administration clearly does not care about the Neutrality Treaty, but the Panamanian supreme court very well might. A lawsuit against the basing agreement already been filed based on Article 325 of the Panamanian constitution, which reads:

Treaties or international agreements that may be concluded by the Executive Branch with respect to the Panama Canal, its adjacent area and the protection of said Canal, as well as the construction of a sea-level canal or of a third set of locks, shall be approved by the Legislative Branch, and after being approved shall be submitted to a national referendum, to be held not earlier than three months from the approval by the Assembly.

You never know! Maybe the Administration will pull out the Guano Islands Act somehow or just declare it a U.S. territory and direct agencies to start spending money. I doubt it, and stranger things have never actually happened. But this is the second Trump administration.

As part of the convention, the U.K. declared that it “renounces in favor of the United States of America all her rights and claims over and in respect to the Island of Tutuila and all other islands of the Samoan group east of Longitude 171° west of Greenwich.”

SCOTUS has generally upheld Congress’s broad powers under the territorial clause. While the Supreme Court has respected the Covenant, it would likely defer to Congress if it chose to unilaterally abrogate it. For a short discussion of the territorial clause, see here.

Aceso Global, “Panama Country Report: Transition Readiness Assessment,” (July 3, 2017).

U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Medicaid Information Technology: CMS Supports Use of Program Integrity Tools but Should Improve Reporting of Effectiveness,” GAO-20-179 (December 2019). See Table 2 (p. 17) and Appendix III for MMIS cost estimates by state. Low-end systems in Wyoming and Vermont ranged from $30–80 million.

$80 million for Vermont, scaled up to Panama’s population of 4.4 million, and rounded upward to one significant digit.

Ministerio de Salud, “Informe de Ejecución Presupuestaria al 31 de Octubre de 2022.”

The linked source says $4.4 billion, but a better, more detailed source is the official budget for 2024. The $4.9 billion does not include $2 billion in capital expenditures.

Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), Recent Changes in Medicaid Financing in Puerto Rico and Other U.S. Territories (October 28, 2024).

If Congress emulated Puerto Rico before 2019 and imposed an income limit of $7,200, then the share of covered families would drop to a little over 40% and the fiscal cost would fall to around $1.25 billion. The BOTE math is as follows: Take the 2016 maximum benefit of $315 per month. Multiply by 3.7/3 to adjust for an average household size of 3.7 and multiply by 1.3 to adjust for inflation. The $7,200 number comes from Brynne Keith-Jennings, “Introduction to Puerto Rico’s Nutrition Assistance Program,” CBPP (November 3, 2020). For the size of the block grant to P.R., which came to about $1.9 billion, save for Hurricane Maria, see Brynne Keith-Jennings and Elizabeth Wolkomir, “How Does Household Food Assistance in Puerto Rico Compare to the Rest of the United States?” CBPP (November 3, 2020).

See page A-41 of the statistical appendix to the Informe Económico al Gobernador 2023 y a la Asamblea Legislativa. More than half of that spending comprised the federal courts, Homeland Security, and the post office.

An initial federal setup effort — establishing a judiciary, law enforcement footprint, and agency presence — might plausibly run to $2.6 billion. I will add here that the feds heavily subsidize housing and other sectors in Puerto Rico to the tune of $3.7 billion … Congress won’t have to do anywhere near as much for Panama.

The CSS collects a payroll tax of 22% (at least before this year, when it will rise). Using that tax rate, you can use CSS financial statements to calculate the total formal sector wage bill was $14.6 billion in 2023. Applying total Social Security and Medicare tax rates to that figure provides the estimate for payroll tax revenue.

The assumption is not terrible, since roughly 85% of Panamanian workers reported working more than 40 hours per week in 2022. Data from Estadísticas del Trabajo: Encuesta de Propósitos Múltiples, April 2022.

In theory, the EITC raises incomes without changing willingness to work, since you need to work to collect it and benefits rise with income. The NAP, on the other hand, shrinks as family incomes rise.

These figures unrealistically assume that Panama’s existing transfers remain in place — transfer payments currently make up about a fifth of the income of Panama’s poorest decile — and that the rest of the tax system remains unchanged. I am only going to do so much for a blog post.

The Panamanian-American population shakes out as follows: Florida (17%), New York (17%), California (10%), Texas (9%) and Georgia (8%).